Compassion fatigue – does it really exist? By Cheryl Fry

Compassion fatigue is a term that is often mentioned in conjunction with stress and burnout in the Veterinary world. It is defined as the combination of the emotional, physical, psychological, and spiritual exhaustion that can result when veterinary staff are repeatedly exposed to another’s pain and suffering. It suggests that caregivers are tired of feeling too much compassion.

But what if it isn’t too much compassion that is the problem after all? What if, in fact, compassion may be the antidote to burnout?

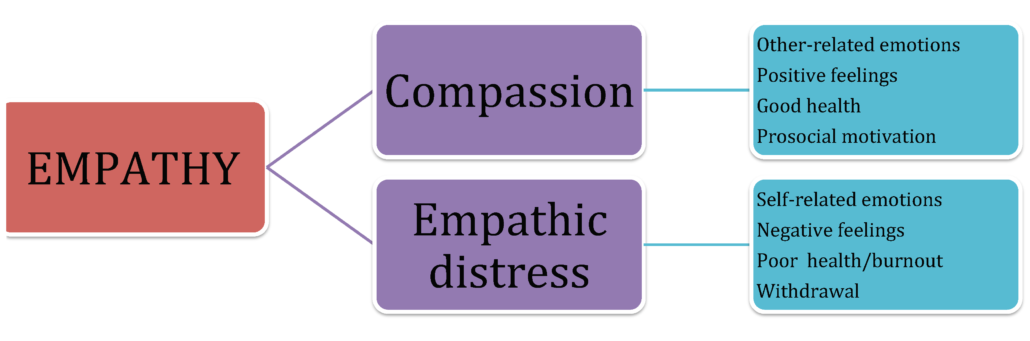

The work of Dr Olga Klimecki and Dr Tania Singer suggests that a new model to describe the interactions between empathy, compassion and burnout should be considered.

It may not be compassion fatigue that we are experiencing as carers, but instead empathic distress or empathy fatigue.

Recent research shows that compassion is a positive thing

- Compassion is defined as a strong feeling of concern for another person’s feelings of sorrow or distress and the motivation to alleviate suffering and/or help.

- When you feel compassion for the suffering of someone else, the neurological pathways that are activated in your brain are those associated with positive emotions such as loving kindness and warmth.

- Compassion can stimulate feelings of courage and determination, and a desire to want to help others. This is relationship building.

- When you feel compassion for someone, it is not exhausting because you are not personally distressed. You can feel positive emotions such as loving-kindness even during those times that you witness suffering.

It is the excess of empathy that can cause problems in carers

- Empathy is defined as the ability to understand and share the feelings of another.

- When you feel empathy you share in another person’s emotions. While you understand that the pain is not yours, the pathways that activate in your brain are the same network that would activate when you personally experience pain. This process allows you to have a shared understanding of the suffering of others, but can also lead to personal suffering and stress.

- Empathy may develop into compassion, but doesn’t always. It may not lead to any action to help the person that is actually suffering.

- When you feel empathy for suffering, it is very emotionally draining, as you are also suffering.

- Being empathetic with someone in distress produces negative emotions such as sadness or anger, and can lead to mental and physical exhaustion – or burnout.

- Empathic distress, where you continue to feel the suffering of others, tends to be isolating. You become overwhelmed by all of the negative emotions you are feeling, and seek refuge in being alone.

Empathy is a vital first step in the chain of emotional responses that lead towards feelings of compassion, or empathic distress. The trigger for both pathways in your brain is the same, but it is how you respond that will determine whether you are exhausted from empathy overload.

An example

- Imagine a client is sad because their dog has just been diagnosed with terminal cancer.

- As a caring Veterinarian, your first reaction would be empathy. You share the feeling of sadness with your client.

- Empathy is the first step connecting you to the emotional state of your client. This is both normal and desirable for building the client relationship.

- The next step depends on your personality, your emotional state, the situation, and your self-awareness.

- Do you focus on your own sadness and allow it to overwhelm you, or do you focus on trying to make things better for your client? By shifting the focus away from yourself and onto alleviating the suffering of others, you activate the compassion pathways.

- If you react with compassion, you will feel concern for your client and attempt to alleviate their suffering in any way that you can. Your tone of voice, the way you explain their options, your simple acts of kindness during this difficult conversation, may all help make this moment easier.

- If you react with only empathy, you may be overwhelmed with your own sadness and are therefore unable to support your client, and may in fact need to withdraw from the situation.

If empathy fatigue is the problem, how do we avoid it?

- Drs Klimecki and Singer have found that both the empathy and compassion pathways in your brain are open to change – there is neuroplasticity. This means that your emotional responses to the distress of someone else are not set in stone – you can change how you respond.

- Simply noticing your own empathetic response to a client’s distress is very empowering. You can acknowledge to yourself that you are sad along with your client, and that this is both a normal and valuable response in a caring veterinary environment. It is OK to feel sad – it makes sense given the situation.

- The key is deciding to not focus on your own sadness, but instead to focus on how you can make a positive difference to this client’s experience. Ask yourself, “What can I do to make things easier for them?” Take the empathy and add compassion.

- By cultivating compassion as a response to the distress of others, you are helping not only your client, but also yourself.

- Training yourself to be more compassionate is possible. You can change your brain, your emotions and your actions in response to the suffering of others.

- Compassion training has been shown to help overcome the empathic distress (empathy overload) often shown by people in caring professions. It may be the antidote to burn out.

Instead of reducing our compassion in the veterinary world, we should be actively cultivating it.

A compassionate person has the capacity to help because they are not overwhelmed by their own distress, but are instead guided by concern and affection for others.

Perhaps it is time for “compassion fatigue” to be more accurately renamed “empathy fatigue”?

References

Klimecki, O & Singer, T (2012) “Empathic distress fatigue rather than compassion fatigue? Integrating findings from empathy research in psychology and neuroscience.” Pathological Altruism – chapter 28; pgs. 368-380

Matthieu Ricard (2012) “Happiness – a guide to developing life’s most important skill”

Kristen Neff (2011) “Self Compassion – stop beating yourself up and leave insecurity behind”